Summary

High-tech digital tools, such as augmented reality (AR), are powerful, creative means for sharing information about archaeology. AR is currently being used in museums to provide a more immersive experience for visitors.

This is important because some artifacts from archaeological sites end up in museums as a way to give context to the cultures involved, but not all of them can physically be there. Here’s a chance for AR to create connections.

Other applications include virtual representations of structures or artwork. AR also has the ability to give additional information to patrons about artifacts or locations. This wonderful enhancement is made possible by headsets and other mobile devices connected to the technology with special apps.

AR is also being used on site in the field of archaeology for informing students and researchers, as well as contributing to the preservation of cultural and heritage sites.

Early Work

Ronald Azuma, one of the pioneers of augmented reality, offers an excellent definition of AR. He states that “an AR system supplements the real world with virtual (computer-generated) objects that appear to coexist in the same space as the real world” (Azuma et al., 2001).

He continued with the definition of an AR system to have the following properties:

1. Combines real and virtual objects in a real environment.

2. Runs interactively, and in real time.

3. Registers (aligns) real and virtual objects with each other.

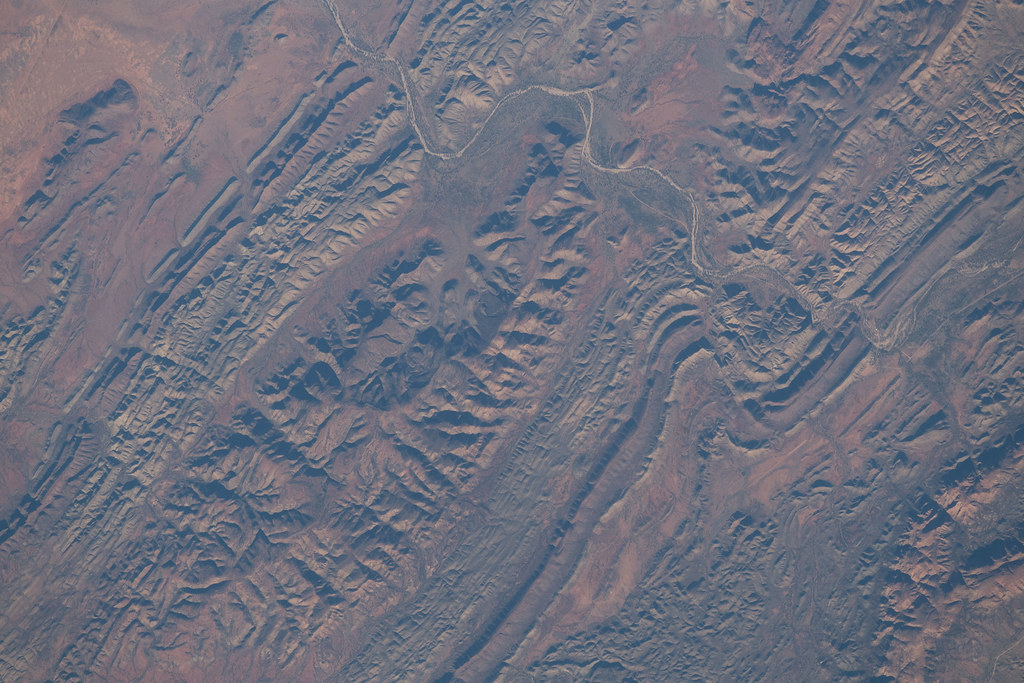

An early idea of using AR in archaeology came from Stuart Eve in 2012, where it was proposed to merge explorations of perception with data-driven maps of archaeological landscapes to create an immersive experience.

The idea was to utilize 3-D models, soundscapes, and social media to reconstruct “detailed models of possible pasts” to better understand ancient cultures (Eve, 2012). This would allow a contemporary human to more fully experience the sights, sounds, and possibly smells of the archaeological sites during the time of habitation. AR would serve as a sort of time machine.

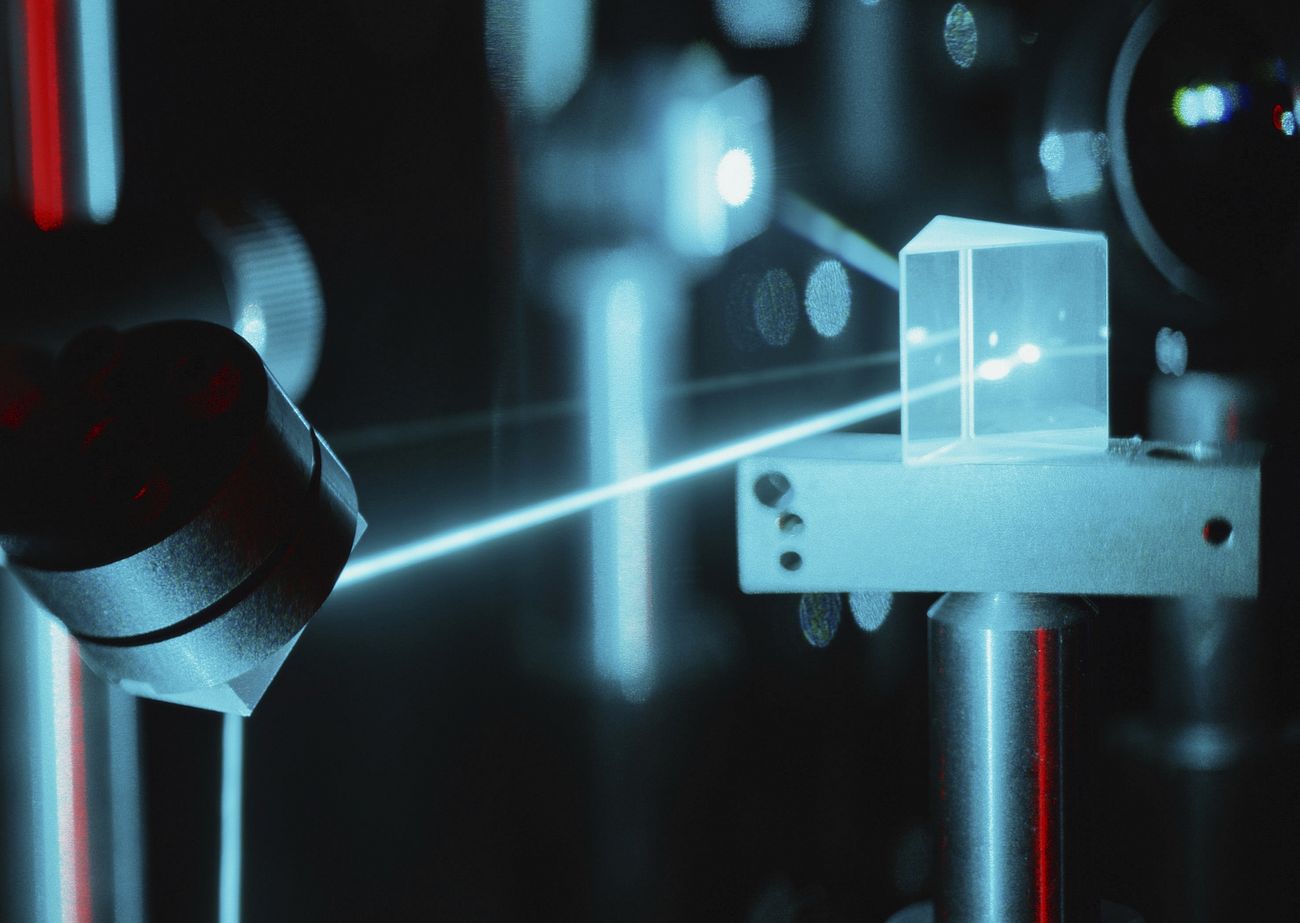

During that same time period, work with lasers as a method of mapping stone structures in Petra, Jordan was being conducted by Jose Lerma and his team. This was part of a movement away from exclusively using photography for creating virtual models.

The use of lasers gave a much more accurate representation of archaeological sites, and this level of precision showed to be beneficial for both recreating models and assessing erosion patterns of important stone structures (Lerma et al., 2011).

Applications

The use of AR at museums and heritage sites is super cool. To get a better idea of what an immersive experience is like, please watch the following one-minute video.

Recent Work

The video from AR Tour on YouTube gives a fascinating glimpse of the experience using high-tech glasses at a heritage site.

How is this even possible?

This is somehow achieved by using lasers, tracking systems, AR programs, mobile apps, and specialized hardware. (And much more.) It’s a good thing that visitors to sites like this don’t need to know how it works.

However, researchers and designers do need to know. Recently, a group of researchers in Spain (Blanco-Pons et al., 2019b) set out to test this complicated network and find ways to improve the immersive experience. Knowledge from this examination can be used to create apps that are more responsive and accurate, even taking weather and sunshine into consideration (Blanco-Pons et al., 2019a).

Implications

This core group of researchers also examined ancient rock art paintings at Cova dels Cavalls in Spain with preservation and information-sharing in mind (Blanco-Pons et al., 2019c). Their goal was to design and implement mobile augmented reality apps that can give us the ability to view these virtually restored rock art paintings. This helps us better understand the purpose and meaning of the original act and the humans that created it.

AR is being used effectively for teaching in many fields, and archaeology is no exception. This technology allows us to “see” dilapidated sites as they once were. It also gives students, researchers, and the general public a chance to “hold” artifacts and “go” places without traveling the world. With fewer hands and feet on these artifacts and sites, they can be preserved for future generations, in reality and virtually.

References

Azuma, R., Baillot, Y., Behringer, R., Feiner, S., Julier, S., & MacIntyre, B. (2001). Recent advances in augmented reality. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 21(6), 34.

Blanco-Pons, S., Carrion-Ruiz, B., Duong, M., Chartrand, J., Fai, S., & Luis Lerma, J. (2019a). Augmented Reality Markerless Multi-Image Outdoor Tracking System for the Historical Buildings on Parliament Hill. SUSTAINABILITY, 11(16), 4268. https://doi-org.ezproxy.snhu.edu/10.3390/su11164268

Blanco-Pons, S., Carrión-Ruiz, B., & Lerma, J. L. (2019b). Augmented reality application assessment for disseminating rock art. Multimedia Tools & Applications, 78(8), 10265–10286. https://doi-org.ezproxy.snhu.edu/10.1007/s11042-018-6609-x

Blanco-Pons, S., Carrión-Ruiz, B., Lerma, J. L., & Villaverde, V. (2019c). Design and implementation of an augmented reality application for rock art visualization in Cova dels Cavalls (Spain). Journal of Cultural Heritage, 39, 177–185. https://doi-org.ezproxy.snhu.edu/10.1016/j.culher.2019.03.014

Eve, S. (2012). Augmenting Phenomenology: Using Augmented Reality to Aid Archaeological Phenomenology in the Landscape. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 19(4), 582–600. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.snhu.edu/stable/23365980

Lerma, J.L., Navarro, S., Cabrelles, M., Seguí, A. E., Haddad, N., & Akasheh, T. (2011). Integration of Laser Scanning and Imagery for Photorealistic 3D Architectural Documentation. InTech. doi: 10.5772/14534 In Wang, C.-C. (Ed.). (2011). Laser Scanning, Theory and Applications (pp. 413-430). InTech. doi: 10.5772/630

Leave a Reply